When we first started boating, we made the decision—partially based on high-minded philosophy and substantially based on a lack of budget—to make do without much in the way of instrumentation.

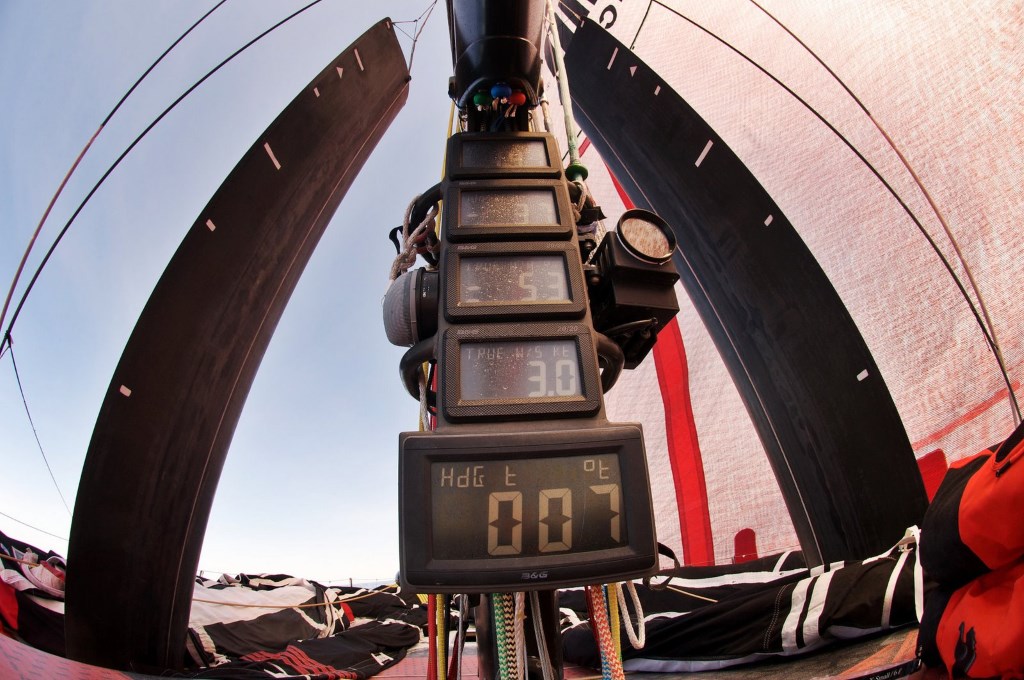

As I trolled the sailing forums in the early days, I heard plenty of stories. People who used their GPS and autopilot to navigate to the next buoy…and then ran into it. People who kept losing races while staring at their wind instruments, convinced that they were sailing an ideal VMG, only to have others point out that their sails weren’t hoisted all the way. Of course, this is not to say that instruments are bad. A quick look at the mast of a serious offshore race boat will show that sailors at the top of their games are consuming a lot of data. We just wanted to learn the basics first.

Image copyright Rick Deppe/PUMA Ocean Racing/Volvo Ocean Race

We still run pretty lean, but there are a few instruments that I consider must-haves, and this weekend, despite some pretty great sailing weather, we fixed them.

Compass

We mostly sail in a protected bay and our compass heading isn’t usually all that important, but when we tried to sail back from Sandy Hook in a dense fog during our delivery, we were really glad to have it. It was eerie to have no point of reference other than a magnet floating in a sphere full of petroleum distillates, but it got us home. Since then, that compass has gone downhill. Well, it was never really that great (it had an air bubble in the top the size of a silver dollar, and the card could only be read from above, which was of little help on a bulkhead mounted compass) but over time the globe became even more yellowed and crazed and the fluid mysteriously vanished. Perhaps the most frustrating thing to me was that it was mounted on a decaying wooden box, designed as a standoff to keep the compass vertical even though the bulkhead is angled.

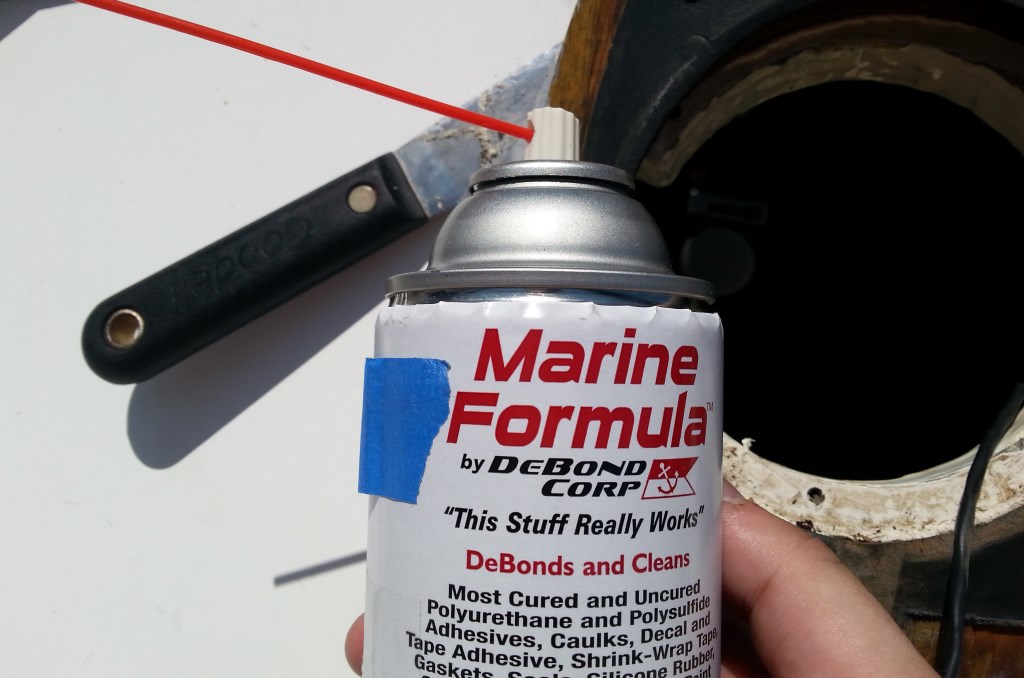

There were four long screws holding the compass to the wood, and I think mechanically fastening it to the bulkhead, but after removing them it was clear that there was also some kind of sealant holding it on. After replacing our portlights between 4200 and 5200 times, I didn’t mess around and went straight to the DeBond and my sharpened putty knife. The knife is about a half inch shorter than it was previously—a casualty of the Portlight Debacle of 2016—but I ground a new leading edge on it and thinned it down again with a belt sander. It made short work of the adhesive.

The remaining compass hole was oriented ~90º off of the proper orientation for my new compass, but the hole was also too small overall, so I was able to consume most of the port-side extension when I recut it.

I obtained a scrap of Starboard from the yard, took it home, and machined up a new plate to make the installation tidy and cover up all of the old holes and discolored gelcoat. Jen and I returned on Sunday, took a handheld jigsaw to the bulkhead (always nerve wracking) and mounted the new compass.

Starboard is made of high-density polyethylene (HPDE) and can’t be glued by normal humans, so it’s mostly fastened to the bulkhead with screws, but we also threw a layer of polysulfide behind it to seal it.

I’m happy with it. And yes, I’ll get to the teak eventually.

This is the same model of compass that we installed on Fortuitous I, and one of our favorite things about it is that it makes for a cool nautical decoration on the inside of the boat.

Depth Sounder

We sailed the 22 for years without a depth finder, mostly by ramming into the muck, raising the keel, and continuing on in a different direction. With our current fixed keel, however, it is preferred to avoid running aground, and having a depth sounder is helpful in that regard.

Last year, our depth finder got pushed through the bulkhead while racing. It was never clear to me exactly how it was supposed to be mounted, or why I couldn’t get it to go back together reliably. While I was dismantling the compass, Dale walked by and I asked him to take a look at it. He immediately identified that the part that kept getting pushed through was supposed to be permanently affixed to the bezel that continued to remain on the outside of the bulkhead, which is why no amount of torquing down the thumbscrews on the inside would hold it in place.

The fix was relatively simple…I just removed the bezel and epoxied the electronic part to it. I left it overnight with some bungee cords as makeshift clamps and taped over the hole.

It went back in without much trouble, and now the thumbscrews can actually do their job.

Stanchion Re-bedding

While not an instrument, I figured that if I was going to break out the epoxy, I might as well fix the leaking stanchion. This followed the same process that we used on the 22 when we redid our lifelines and stanchions:

- Remove the offending stanchion.

- Drill out the holes with a big bit. I used a 9/16 inch.

- Inspect the deck core for moisture/rotting. (none)

- Tape over the bottom of the holes.

- Fill the holes with thickened epoxy.

- Give up on sailing tomorrow. This epoxy takes 24 hours to set.

- Clean up the deck side, chiseling/sanding the epoxy flush.

- Use the stanchion as a guide to drill new, much smaller holes through the epoxy plugs.

- Lightly countersink the holes.

- Clean up the area. Give it another light sanding and wash it and the stanchion base with acetone.

- Butyl up your stanchion and screws, and secure the whole thing to the deck by turning the nuts from below while holding the bolt heads steady.

We missed out on some sailing, and, as always, these projects took more time than expected, but I’m glad to have our instrumentation (and lifelines) back in working order.