As mentioned in the previous log entry, we bought a new boat. I’ve been intentionally sketchy on some (most) of the details, because it didn’t really feel like it was ours yet. But I guess if anything is going to make you feel like you own a boat, it’s making your first voyage together on the longest and most elaborate trip of your sailing career, bringing her home. This would require sailing in the ocean, traversing an inlet, and motoring through a canal—none of which we’ve ever done. Throw in seven drawbridges, a tidal current that’s offset from the tide by hours, and a virtually unlimited number of unknown unknowns, and you’ve got yourself, well, something…

The boat was in Sea Bright, NJ, on the Shrewsbury River, which runs north from Oceanport, up toward the Atlantic Highlands and Sandy Hook Bay. We had to get her back to our new marina in Cedar Creek, about 50 miles south by water. Preparations began even before the purchase was complete and I had been poring over charts, tide tables, and weather reports. We had limited time to get the boat out of her old marina, so I’d been looking for a weather window. The forecasts were saying that there wouldn’t be much wind on Friday and what wind there was wouldn’t be on our nose. There are strong tidal currents on the Shrewsbury though—we wanted to take that out of equation in calculating our travel time to slack water at the inlet and possibly conserve an hour of sleep on Thursday night, so we set things in motion to leave Thursday, anchor at Sandy Hook that night, and complete the bulk of the delivery on Friday. I didn’t sleep at all on Wednesday night.

Thursday, May 8

We got up early on Thursday to complete preparations and start the trip. I took care of some paperwork regarding the boat registration and stocked up on supplies while Jen finished packing. We drove separately to Cedar Creek so that we could stage a car there, and got some things off of our old boat. The lines that had been in our new slip were gone, so I guess they weren’t a gift, and we tied on some docklines so that we’d have something to grab on to when we arrived. At some point I realized that our chart of Barnegat Bay isn’t a complete NOAA 12324, but just a zoom-in of one part, so I got the full chart to take us all the way from Sandy Hook down. I ran in to Captain Mike at the chandlery, and he didn’t seem to think that our plan was absolutely insane, which was reassuring.

We dropped off the car at Cedar Creek and took the truck up to Sea Bright. I’m not really familiar with that stretch of New Jersey, and somehow got into the express lanes on the Parkway, which caused me to miss our exit. Jen used her telephone to Google us back, which involved diverting from the highway into some kind of performing arts venue and driving on the wrong side of a divided “service vehicles only” road to do a U-turn. It worked, and we were guided on the scenic route to the marina, driving over the Sea Bright Bridge that would shortly open at our request.

We loaded in and gave the cockpit a cursory wash. We forgot to bring our boat stove, so I made a quick trip up to the hardware store to buy propane for the camping stove that came with the boat. We’ll be switching this out with an alcohol stove as soon as we get a chance, since hand grenades of propane don’t make the best marine fuel, but at least we’d be able to get a hot meal. I fired up the engine and we very calmly cast off the lines and motored out of the slip as if we knew what we were doing.

And then the fog rolled in. Or maybe it had been there for a while and we were so focused on the boat that we hadn’t noticed, but either way, we were enveloped in a misty stew and I asked out loud if we should even be doing this.

When we got to the Sea Bright Bridge and asked for an opening, the bridge operator cheerily responded in a sing-songy, “I-can’t-SEE-you!” We got through the Sea Bright and Atlantic Highlands bridges, and motored out into Sandy Hook Bay. We were trying to avoid something on the chart called a “fish trap area” and were creeped out to see some kind of large barge or something in there, with a whole bunch of floating boxes anchored or tied behind it. We eventually found Horseshoe Cove with the help of Jen’s telephone. Captain Mike had told me that the “horseshoe part” was gone, which went a long way toward reconciling what we could barely see with what was on our charts. With a predominately easterly wind, we were still sheltered by Sandy Hook itself, even without the sandbar that used to complete the horseshoe shape to the west.

Amazing new thing: With a depth sounder, you know how deep the water is.

We’ve never had a depth sounder before, and were able to scout out the topography a little bit before anchoring. The anchoring process was surprisingly smooth, despite the fact that we were on an unfamiliar boat. Getting a Danforth to set has historically been tough on our relationship and our little Manson Supreme was a big upgrade on the 22, but we dug it in firmly on the first try and didn’t budge an inch.

Amazing new thing #2: On a 27′ boat, not only can you stand up inside like a fully-evolved human, but you can also sit at the dinner table like grownups and have a meal. Our 22 technically had a table, but I think we only ever used it once, since sitting at it made me feel like I was riding in one of those helicopters or police cars outside a Kmart that goes up and down and makes a noise when you put a quarter in it. Sleeping was also drastically improved, since the starboard settee folds out into a double bed that’s actually big enough for two adults.

That said, I didn’t sleep much. I was going over plans and contingency plans in my head, trying to make sure that I knew everything I could know before we crossed the imaginary line into the ocean. I had been reading Eldridge over and over and checking my math against the NOAA tide and current tables in the days leading up to this, and had calculated that if we left at 0600 and averaged 5kts, we would make the Manasquan Inlet at slack water around 1200, when there would be the absolute minimum amount of current. We’ve heard horror story after horror story about inlets, since our home waters are so close to the notorious Barnegat Inlet, and I have what I hope is a healthy fear of any place where the ocean tries to squeeze through a slot of water a hundred yards wide. By all accounts, Manasquan Inlet is much easier to navigate than Barnegat, since it lacks the ridiculous shoaling inside the jetties with a constantly shifting channel, but catching any inlet at full bore or with wind set against the tide can be a mess. The only part of it that you can control is when you run it, and I was doing my best to latch on to that.

Friday, May 9

I got out of bed at 0500 and rechecked the weather reports. The wind predictions hadn’t changed, but the fog was still in. We seriously considered staying, but the forecast for Saturday was worse, with rain and thunderstorms predicted. Sunday was stronger winds from the south, making sailing impossible. Given the success we’d had at finding Horseshoe Cove in the fog, we hauled anchor and crept out of the cove with the engine.

At some point, we crossed some invisible threshold where the waves became swells and the kind of marshy beach smell became a crisp clean actual ocean smell. We would have loved to have seen the point of Sandy Hook fade off our transom and the nearly infinite expanse of ocean ahead of us as we pointed the boat toward Spain and made our way away from the shelter of land…but we couldn’t see a damned thing.

Using mostly Jen’s telephone along with the charts and compass, we turned south and started making our way down. Around a half mile off offshore, we tightened up to 200° or so to follow the coast, well out of the shipping lanes but far enough off the beach that we didn’t have to worry about depth. The fog was eerie, but fascinating. We couldn’t see anything in any direction—just a few hundred yards of ocean all around us. Having only sailed in the bay, we’ve never had to really sail strictly to a compass heading, and I found it frustrating initially. With nothing to look at, there was no indication that you were turning other than the compass itself, and it was tough to both keep a watch and mind the heading. The boat was handling well though, and was very stable in the light swell. We eventually started to work into a rhythm.

That rhythm was abruptly disturbed when a horn sounded directly in front of us. Not like one of those canned air horns or the little trumpet horn on a fishing boat. This was the chesty, thunderous horn of a ship, firing off like its team had just won the Stanley Cup, and we couldn’t see it. We attempted to sound our horn in return and it whimpered a sad, barely audible “ha” since it had no air. As we scrambled for the backup horn (which we had, and it worked) I saw a dark shape emerge from the fog. It just looked like a black cube, taking up what seemed like half of the horizon. I couldn’t tell what it was, or, more importantly, where it was going. I squeezed the tiller like I was trying to crush it, literally not knowing which way to turn. I picked up the handheld VHF with my free hand and hailed them in some stupid way—Jen and I were beside ourselves in the moment and neither of us could remember exactly what I said even minutes after it happened, but it was something along the lines of “vessel blowing your horn at a sailboat off of Sandy Hook, this is that sailboat.”

Whatever it was, it worked. The captain responded and identified himself as a dredge, and let us know that he was at all-stop, dead in the water, but that we were headed straight for him. I turned drastically to starboard and told him that we were now heading two-seven-zero, and he confirmed that we were good. He had seen us on radar, but obviously, we couldn’t see him. He also informed us that there were more dredges along the coast working about that distance from shore. I thanked him, and as soon as we got around him we bumped out another mile.

I didn’t expect to see anything that big that close to shore and that far out of the shipping lane, but I admit that I hadn’t thought of a dredge. At least it wasn’t a container ship going 22kts and not minding the radar.

It took a long time for us to calm down.

After an hour or so of uneventful transit, I handed the helm over to Jen. I went below, tore off my life jacket and foulies, and used the head. In those few minutes, I started to feel seasick, which is not something I’m used to, and that reminded me that we never put up the sail. I had been so distracted by the ocean and the fog and making good time (and now getting run over by huge ships), I forgot that the whole reason we chose this weather window was so that we could sail.

I ate some bread and drank a soda, and then prepped the main. I figured that with the light wind, we’d be too slow on sails alone to make slack water at the inlet and that having the jib out would be a liability since we already couldn’t see anything, but that the main would help with the boat motion. I tucked in a reef before hoisting it, just in case we should get hit with a freak storm or something, and having it up did help quite a bit. We could also trim it to overcome the boat’s unwillingness to steer to certain headings given the wind and sea state. We tried for a long time to get the tiller pilot to work, which would have been far less fatiguing than just steering to the compass (especially now that the silhouette of every distant wave through the fog looked like an oil tanker bearing down on us at speed) but we couldn’t make it work. It was doing something, but it wasn’t holding a course in any kind of way that I could understand, so we gave up and steered by hand.

Jen took a brief nap, although I called her up on deck in short order when we went through a field of fishing buoys and I needed a second set of eyes. After a few more hours of calm motorsailing, Jen said that I could go take a nap if I wanted, knowing that I hadn’t slept for two days at that point. She said that it was easy to sleep with the gentle motion and the thrum of the diesel, so I did.

I’m not sure if I actually slept, but I did dream. Of what, I don’t know, but when Jen called for me, I had that sensation of recalibrating into this reality. Still in my gear, I leapt up to the cockpit to see what was going wrong, and Jen calmly said “Land Ho” and pointed. The fog had lifted, and we could finally see the beach. What’s more, she gestured ahead and said “You should check this, but I also think that’s the buoy for the inlet. I hear his bells.” I picked up her telephone to verify, and in my somewhat dazed state, said:

“You found the Baltimore Shrimp Box?”

Jen is still laughing about this.

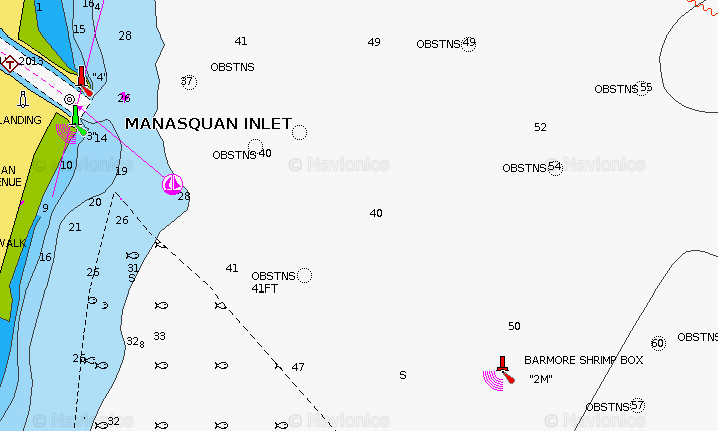

I have no idea what it means or what it is, but it was hilarious to her as a non sequitur. Upon further inspection, it actually said Barmore Shrimp Box, but the text was somewhat obscured by a marker icon in our view at the time (although the icon was, in fact, for the Manasquan Bell Buoy, which Jen found singlehandedly).

Either way, we arrived at the Baltimore Shrimp Box about an hour ahead of schedule. This meant that the current wasn’t dead slack, but it was moving very slowly. We approached cautiously and observed a small powerboat navigate the inlet without any difficulty whatsoever, so we decided to go for it. In those nearly ideal conditions, there was nothing to it. While our first jaunt in the ocean may have started in a blind panic, it ended as easy as a Baltimore Shrimp Box.

Two tribulations down, we set about navigating the Manasquan River. We had to wait for an opening at the railroad bridge, which I think is pretty unusual (railroad draw bridges are usually open for boat traffic, and only close when a train needs them, unlike road draw bridges). If I saw one of these on your model train set, I would have said it looked fake. The Route 35 bridge follows it immediately, and it was a more typical double leaf bascule like we’re used to.

After that it was a placid run up the Manasquan River to the Point Pleasant Canal. I’ve heard mixed things about the canal: it’s narrow, turbulent, the current can flow over 4kts, and it has corrugated steel sides so there’s nowhere to bail out if something goes poorly (although they do thoughtfully provide escape ladders). There are also two lifting drawbridges on it: the Route 88 Bridge and the Bridge Avenue Bridge (which presents a sort of chicken-and-egg naming issue). The bridge supports can supposedly do weird things with the current and timing the openings can be tense, especially if the current is with you, pushing you toward a closed bridge. Lift bridges are disconcerting too, in that they only open high enough for you to get through, adding to my already substantial paranoia that my mast isn’t going to make it. I’m not sure if this is apocryphal or not, but I’ve heard from several different people that the operators of these bridges are the best that New Jersey has to offer (specifically because of these known difficulties), and they did a great job with us. We’d also timed it pretty well, with a slight current against us, although in both cases it wasn’t necessary for us to slow down, and the bridge attendants talked us through it all fairly easily.

As we cleared the canal, the water opened up on to Bay Head, where the Metedeconk River meets Barnegat Bay. We’d always wanted to see the Metedeconk, but with our home port so tantalizingly close we didn’t spend any time enjoying the river and just followed the familiar ICW markers south.

The one downside was that the fog was back…more point to point navigation with our charts and the compass, since we often couldn’t see the next marker. On that side of the bay, it’s imperative that a sailboat stay in the channel since most of it is shallow flats, although the winds were still light. What made 2-3ft of swell in the ocean produced little more than a ripple in the bay, so maintaining a course was easier.

As we went through the Mantoloking Drawbridge, we sailed past the point that had previously been our most northern foray, back from 2011 when we ditched out on Woodsy the Owl to sail north from Cattus Island. Obviously, we’d crushed the record the minute we started this trip, but crossing that line was a dramatic reminder of how limited our cruising range was with a 22.

We passed Kettle Creek and Silver Bay, although we couldn’t see them. I was worried that we wouldn’t be able to see our old standby drawbridge: the Mathis Bridge (the only drawbridge we’d ever used before this trip). Jen actually plotted out on the chart where to call them so they could start looking for us. When we reached that point, I called, and we got no answer. I tried again. I started to doubt that 13 was even the bridge channel, and tried on 16. We tried from the fixed VHF. No answer. We got all the way up to the bridge and started fumbling around, trying to stay in one place (this was the first time that I ever attempted to operate an inboard in reverse other than backing down on the anchor the night before, which was, uh, enlightening). After half an hour of waiting with no response, I remembered that when I was researching the trip, I’d found the schedule of bridge openings and that there was a phone number. In the winter there is so little boat traffic that some of the state’s drawbridges don’t open unless you give 24 hours notice by telephone for someone to be there. I called the number, expecting to get Bridge HQ, but the guy answered “Toms River” and it turned out that I was speaking to the bridge attendant himself. I explained that I’d been waiting for an opening and couldn’t reach him on two different radios and he said, “Oh, I must have left my radio off when I was cleaning it.” It then occurred to me that being a bridge attendant on a foggy weekday in the off season must be a pretty awesome job if you like crossword puzzles.

South of Rt 37, we were in our real home waters. We passed the Toms, took the long way around Good Luck Point (we were too close to victory to require a tow off of a sandbar at this point), and eventually got far enough to make out Berkeley Island County Park through the fog. It’s not a great photo, but this was a big deal for us.

We motored up the Cedar Creek to our new marina, and I faced the final challenge of this odyssey: pulling into a slip with an inboard keelboat directly next to an 8 bazillion dollar Island Packet…with a dozen people watching. There’s still time, but I did not win our sailing club’s Dillon Dock Meter Award for the most outrageous crashing into a dock just yet. With some last minute guidance from Val and Captain Mike, we put that boat into the slip like we’d done it a thousand times. Swish. Also, for the first time in our sailing careers, we came into our marina and were not looked at like we pulled in to a biker bar on a hot pink Vespa with a side car. We were greeted by our best sailing buddy and our ASA 101 instructor, who were happy to finally see us in a boat that could realistically sail in an ocean.

It probably goes without saying that this was our most intense sail to date. We broke all kinds of personal records for speed, endurance, big water, and navigation, and our new boat performed admirably. Like a big 22. The trip was not without issues, and I feel a little ripped off that we sailed in the ocean but only got a view of it within a radius of a couple hundred yards, but we made it, and we’re better sailors for it. Jen wanted me to title this boat log entry “Baltimore Shrimp Box,” which would have been great, no matter how undescriptive it might have been. I went with Deliverance, not after the “squeal like a pig” movie, but because this was our first boat delivery, and maybe a little because of the other definition: being set free. I think having a more substantial coastal cruiser, with the skills that we’ve been honing for years on our 22, is going to open a lot of opportunities for us.

More photos are in the gallery, here.

Congratulations Chip and Jen! Great job. We're very happy for you and glad to hear you made it to home port safely. Here's wishing you years of good sailing on your new vessel. Agie and Steve

Thanks guys!

Jen was right about Baltimore Shrimp Box . . . congrats.

Jen's usually right. Thanks man.

Congratulations!

Thanks Donna!

Nice write up Chip.

Congrats to you & Jen. Every boat delivery I have been on has always raised my confidence level.

The last one I crewed for was Cape May to NYC.

Keep raising the bar!

Thanks Caleb. It was weird how the stuff I was nervous about turned out to be not that big a deal, but the stuff we didn't think about turned out to be a hassle.

Awesome read and I can’t imagine how awesome that trip must have been. Trailering a boat home cannot compare to sailing, motoring, or how ever on the water. Congrats on the new boat, a great trip, and all the fun ahead!

Thanks man! In some ways, I'd be more freaked out by towing a boat that far, but sailing (or motor sailing) her home was certainly pretty intense for us.

Great job, and I laughed at “we came into our marina and were not looked at like we pulled in to a biker bar on a hot pink Vespa with a side car”.

RESPECT.

Also, after reading this and seeing all that mist, you DEFINITELY want an AIS VHF. AIS would have shown you the dredger, the bearing, the COG, the speed (0.0 kn) and the CPA, which would have been “thump”. You could have diverted 5 degrees 2 NM off (assuming no shoal water or other issues) and never have seen them, but you would have known they were there.

Oh, the places you’ll go.

Yeah, AIS would have been a huge help in that scenario. Although it does make for a better story when you can say "In my day, we used to run down ships in the fog with only a bell and a busted air horn to protect us."

We're super excited to stretch our legs in a bigger boat though. Thanks for reading and commenting!